Here’s classic volume of revolution problem:

Determine the volume of the solid created when the region defined by

, the line

, and the x-axis is rotated about the x-axis.

Typical calculus classes present TWO ways to compute such volumes of revolution–orthogonal and parallel to the axis of rotation. In this post, I argue that with substitutions involving differentials, you can actually get your choice of FOUR integrals to solve. Hopefully one of them will be easy to solve. Here’s how.

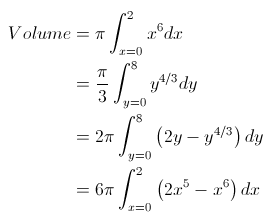

Slicing the volume ORTHOGONAL to the x-axis creates discs with radius and thickness

giving an original (orthogonal) volume integral

.

Method 1) I think the approach most familiar to most students is to substitute using to get

Method 2) Here’s my suggestion that I don’t see too many people use. Consider substituting for the differential using to get

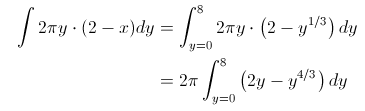

Using the method of cylindrical shells, slicing the volume PARALLEL to the axis of rotation creates a series of annuli, each with radius , thickness

, and height

, giving an original (parallel) volume integral

.

Method 3) Substitute into this to get

Method 4) Or you could use the other differential, , to get

CONCLUSION:

No matter what approach you take, it’s important for students to understand that there is no single approach that will will work well for all volumes. Increasing the number of representations available for manipulation generally should increase your chances of finding one that’s easy (or at least easier) to solve.

In the end, I just think it’s pretty that all four of these integrals are exactly equivalent even though they really don’t look much alike.